In the first two steps of the Searching for ANSWERS inquiry learning process, students generated their inquiry questions, conducted some preliminary research, and developed their hypothesis or thesis statement. It’s now time for them to search and seek information that will prove their theory or claim. Depending on the content area and purpose, this process can take several different forms.

Conduct Experiments

For science classes, these methods and strategies may involve experiments to test out a hypothesis. Technology tools are playing an increasingly important role in this part of inquiry. For example, digital sensors, probes, and microscopes can be connected to laptops to automatically populate the collected data into a spreadsheet. Students can use collaborative spreadsheets, like Google Sheets, to collect this data from multiple lab groups, or even from classes across the globe, in order to generate much larger datasets from which to draw conclusions. The Arduino Science Journal is a free app, originally created by Google, that enables students to use their phone or other mobile device as a sensor to collect data on motion, sound, and light. When used with other external hardware, students can also conduct experiments on pressure, magnetism, heart rates, and more. Free online simulations—such as PhET (Tips), a project from the University of Colorado Boulder—provide many interactive simulations that students can use to test out ideas and learn concepts related to physics, chemistry, biology, and math.

Explore Primary Sources

For some inquiry questions, especially in humanities courses, like history and art, students may seek answers by looking at primary sources. DocsTeach is a great resource for searching the thousands of primary documents from the National Archives. Students can also access primary images, texts, and recordings in digital formats at the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution. Many museums now provide access to their collections online, such as the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. For links to more online museum resources and collections, see MCN’s The Ultimate Guide to Virtual Museum Resources, E-Learning, and Online Collections.

Interview and Survey

In our globally connected world, students now have greater access to connect with firsthand witnesses, experts in the field, and others who can offer insights into their investigation. To connect with these resources, students can hold online interviews, send digital surveys, and correspond via email. For example, students can use videoconferencing programs, such as Zoom, to interview a survivor of the Holocaust or virologist from the CDC. Students can conduct opinion polls or collect necessary information by using online survey tools, such as Microsoft Forms or Google Forms. This data can be compiled into a corresponding spreadsheet where it can be quickly sorted, filtered, graphed, and analyzed.

Observe Events

Students can also use technology to seek information by personally observing events. For example, live cam sites—like the San Diego Zoo Live Cams and Explore.org Livecams—can provide students with the opportunity to collect observational data about animal behavior and other natural phenomena. Students can also watch a wide range of events that have been recorded and shared on social media sites, like YouTube. For example, they can watch storm chasers recording the formation of a tornado, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and NASA spacewalks.

Search Online

The most common way we seek answers for our inquiries (personal, academic, and professional) is to search online. The opportunity for students to find information to their questions has never been greater. Not long ago, students were limited to the resources that were available in their classroom, school, and local libraries. Today, there is a vast wealth of information available for students. This convenient availability of information has revolutionized the potential for students to dive into inquiry learning. However, this vastness has also created its own challenges, including how to effectively find relevant information among the trillions of resources available and how to be sure information found is credible. The challenge has shifted from finding enough information to sifting through the overwhelming amount of content available and locating worthy content. Learning how to address these challenges will not only help students answer their inquiry question, but also help them become critical consumers and responsible producers of information.

Teach the Skills to Access and Evaluate Information

Inquiry learning provides an excellent opportunity to develop our students’ digital, media, and information literacy skills. These skills include the ability to use technology to access and evaluate information. To be successful researchers of online information, students need to learn how to use online search strategies as well as how to become credibility detectives. The following are strategies and digital resources that you can use to help students effectively locate and verify the credibility of information they will use to prove their thesis or hypothesis. You can use our Search and Seek Information template to guide students during this third step of the inquiry process. The following posters can also be used to teach your students related concepts: Effective Search Strategies: Google, Effective Search Strategies: Boolean Operators, Be a Credibility Detective: Verify the ABCs, and BIAS. Feel free to make copies of these resources and modify them as needed for your learners.

Plan and use search strategies, methods, and resources.

The following strategies and tips will help students locate relevant information when searching online.

Start With Trusted Databases and Collections

Before searching the World Wide Web, students should start by searching trusted online databases and collections. These databases are typically subject-focused, vetted for credibility, and limited to quality resources. With databases, students can focus on locating relevant information rather than having to also confirm if the information is credible. Also, by starting with databases, they can develop stronger background knowledge that will help them identify misinformation when they search the Web. If you have access to a school library media specialist, they can help guide your students to accessing and using the school, district, and/or state database subscriptions. There are also free databases and credible collections available online. Here are a few examples to get you started.

For Older Students

- 101 Free Online Journal and Research Databases for Academics (Scribendi)

- List of Credible Sources for Research (Scribbr)

- Most Reliable and Credible Sources for Students (Common Sense Education)

- Free Publicly-Accessible Databases (University of California, Santa Barbara Library)

- Freely Available Resources for Research (University of California, Berkeley Library)

- Google Scholar (Google)

For Younger Students

Use Search Engines

Once students have gained a stronger understanding of their topic from trusted sources, they will be more ready to search the Web, where they will also need to verify the credibility of the information (see the ABC process below).

There are many search engines available. While Google dominates the search-engine market, it still only indexes less than 5% of the Web. For this reason, it is important for students to learn the importance of using multiple search engines, as each engine collects and categorizes information in different ways. Some suggested search engines for older students include Bing, DuckDuckGo, Google, and Yahoo!. There are also search engines designed for younger students, such as Fact Monster, Kiddle, and KidzSearch.

Refine Your Results

For both online databases and search engines, students will likely need to refine their search in order to find the most relevant information from among the overwhelming number of sources available. There are two main ways to search: using natural language or Boolean. Natural language is used by typing in a question or key phrase. While natural language is supported in most databases and search engines, Boolean search strategies can be more effective. In this strategy, you use key words along with the Boolean operators AND, NOT, and OR to narrow and broaden the scope of the search.

Examples

- Natural Language: Why is the timber wolf population in Minnesota declining?

- Boolean: “timber wolf” AND Minnesota AND population NOT basketball

Even older elementary students can learn to leverage Boolean operators. To help them understand this concept, play Boolean games before applying these concepts to their inquiry searches. For example, students can first try different search operators in Google and note how it narrows or broadens the number of results that are returned. They can then participate in a challenge to see who can come back with the fewest number of relevant results.

For younger learners, it can help for them to also practice the concept by “searching” their classmates. In this game, students imagine their classmates are sites on the Web. Students take turns “searching” the class using Boolean operators. For example, the student who is searching would first call out for “jeans,” and anyone wearing jeans would stand up. Then, the student would call out “jeans AND red” and those without red on would sit back down. Younger students are often confused that AND narrows rather than broadens results, so this activity helps them see how this logic works. You can also teach them chants, like: “AND, NOT, OR…which gives you more? OR gives you more!”

Students can use the following strategies and tips to refine their search results.

Boolean Search Tips

- Use key words. Start with the most important key word related to your inquiry. Even though millions of results may come back, the source to the answer may be listed in the top results.

- Example: wolf

- Add additional key words to narrow the search. The space between each word is recognized as the Boolean operator AND, so adding more key words will reduce the number of results.

- Example: wolf Minnesota habitat

- Use quotation marks for phrases. Because the space between words is seen as AND, use quotes to keep words in a phrase together in the order they appear within the quotes.

- Example: “timber wolf”

- Use OR between key words to broaden the search. Use OR to add key words that are similar in meaning so that it pulls sources that use either term.

- Example: wolf OR “canis lupus”

- Use a hyphen to exclude words. A hyphen in front of a key word is recognized as the Boolean NOT. This reduces the results by excluding sources that contain that word.

- Example: “timber wolf” -basketball

- Use Advanced Search features. Many search engines and databases have advanced search options to help students use the Boolean operators as well as to narrow by date, file type, and more.

- Example: Google’s Advanced Search

Share the following tips with students for advanced Google searches:

Advanced Google Tips

- Site: Limits search results to a specific site.

- Example: wolf site:mnzoo.org

- Intitle: Searches for the term in the titles only.

- Example: intitle:wolf

- Filetype: Locates certain file types, such as PDFs, Docs, and PPT (see complete list).

- Example: wolf filetype:PDF

- Link: Searches for sites that are linking to a specific site.

- Example: link:mnzoo.org

- Asterisks: Use asterisk (*) wildcards as placeholders for any character(s).

- Example: Wolf *danger*

This will pull danger, dangerous, endanger, endangered, etc.

- Example: Wolf *danger*

Investigate, experiment, explore, and/or observe.

Once students locate a source of information, they will need to be credibility detectives and make sure that their sources are trustworthy.

The internet has made it much easier to produce and distribute inaccurate and even false information. Fortunately, there are many models and checklists available to help students evaluate and identify credible sources of information. While the intention behind these checklists is to help students investigate their sources, research has shown that students too often get lost in the minutia and become automated in checking off items rather than carefully considering the criteria individually, as well as holistically, to determine the overall credibility of the information source.

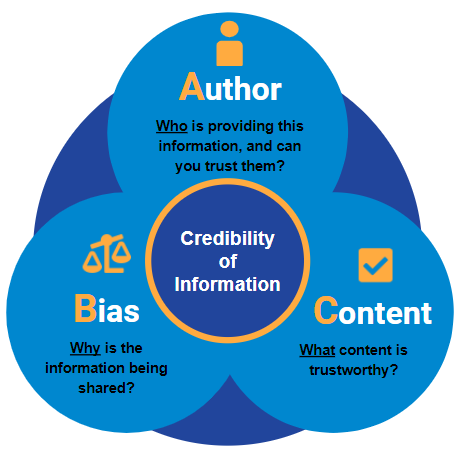

For this reason, we recommend using the ABCs model for evaluating sources. In the ABCs of Checking Credibility, students focus on just three elements: Author, Bias, and Content. Each of these elements plays an important role in determining whether or not a source is trustworthy. However, it is important that students evaluate the sources using the ABCs as a whole and not as completely separate criteria. Each element impacts the other elements. Content, for instance, cannot be explored without considering bias and the credibility of an author. Students cannot simply add up the number of check marks to get a passing score. It all weaves together and must be examined holistically. We must remind our students that the key question they are trying to answer is: “What is the evidence that leads me to trust this information?”

Who is providing this information, and can you trust them?

This is arguably the most important question you can ask about any resource you are reviewing. What are the author’s or publisher’s credentials, and do they have a good reputation as a trusted source? If the student is not familiar with the author or publisher, they should do some research to see what others have to say about them. Consider the strategies below when trying to determine the source of information.

Determine the source (author or publisher)

- Truncate the URL: If you delete everything after the .com, .org, etc., can you identify the primary source?

- Locate the “About” page: What does this page say about the source? Keep in mind that the source will likely only share positive information about themselves.

- Find the Copyright: Is there a copyright statement at the bottom of the page that can help you identify the source?

- Identify the Author: Is there a different author associated with articles or material within the scope of the larger website?

Verify source credibility (author or publisher)

- Research the author/publisher: What do you learn about the author or publisher when you do a web search?

- Check reputation and affiliations: Is the author or publisher trusted by others, and do they have any questionable affiliations?

- Locate works cited: Does the site provide sources for the information they use?

- Read author bio: Does the site provide credentials that affirm the expertise of the author or publisher?

Why is the information being shared?

According to the Cambridge Dictionary, bias is “the action of supporting or opposing a particular person or thing in an unfair way, because of allowing personal opinions to influence your judgement.” Students should avoid using biased information unless they are seeking opposing viewpoints. The first step toward identifying bias is to understand the purpose of the publication. Is it intended to inform, persuade, and/or entertain? Once you know the purpose, you can dig deeper to determine if the information provided is balanced, fair, and accurate or if it is misleading. Sometimes, a source communicates a message that is intentionally biased, but other times, the authors may not even recognize their own bias. The strategies below can provide some ways to check the bias of a source (also see the BIAS poster). For more details on each of these criteria, you can read through the AVID Open Access article, Acknowledge and Identify Bias.

- Balance: Are differing perspectives represented fairly and equitably? Does the placement or timing of a message indicate bias?

- Intent: What is the author’s purpose: to inform, to persuade, and/or to entertain? Is there extreme language? Are there loaded words? Is there mudslinging?

- Accuracy: Do they specify sources or use “general attributions”? Are the “facts” true? Are facts or opinions used for evidence?

- Slant: Is this the whole story? Do the visuals match the facts?

What content is trustworthy?

Once you have determined the credibility of the author or publisher and examined the degree of bias, you will still want to take a closer look at the information itself. Since there may be hundreds of sources that share the same misinformation, it is no longer enough to simply find the same information on three different sources to confirm its credibility. The strategies listed below can help students determine the validity of the content.

- Compare to other sources: Do other credible sources confirm the information you have found in this source?

- Look for citations: Are quality sources posted for the content posted on this site?

- Check date of source: Is the information current and still relevant?

- Verify the evidence: Can you trust the facts and evidence provided?

- Consider the logic: Does the author use faulty reasoning to make a point?

- Evaluate the scope: Do the facts represent the full story and multiple perspectives?

- Confirm facts: Can you validate the information on fact-checking sites, such as Snopes, PolitiFact, or FactCheck?

Extend Your Learning

- New Media Literacy Standards Aim to Combat ‘Truth Decay’ (Education Week)

- Most Reliable and Credible Sources for Students (Common Sense Education)

- Kid-Safe Browsers and Search Sites (Common Sense Media)

- 23 Google Search Tips You’ll Want to Learn (PCMag)