There are various definitions of bias. The Cambridge Dictionary defines bias as “the action of supporting or opposing a particular person or thing in an unfair way, because of allowing personal opinions to influence your judgment.” Wikipedia writes that “bias is a disproportionate weight in favor of or against an idea or thing, usually in a way that is closed-minded, prejudicial, or unfair.” Merriam-Webster writes that bias is “a personal and sometimes unreasoned judgment: prejudice.”

The definitions don’t paint bias in a positive light, using words like “unfair,” “closed-minded,” and “prejudice” to describe it. Despite this potential negative impact, bias is all around us. In fact, most people would agree that we are all biased in some way, and that bias finds its way into our daily conversations and in how we interpret the events around us. It’s in the news, and it’s implicitly embedded in many aspects of our society, including laws and government policies. Our bias can shape how we view the world, and it influences nearly every action that we take as human beings.

Despite its prevalence, bias doesn’t have to be a major negative force in our lives. The first steps in defusing the negative impacts of bias are to acknowledge that bias exists, and then to identify it. After that, our values and norms will determine how we act on that information. To minimize its negative effects and reduce its potential to cause harm, we must develop skills for identifying bias, both in others as well as in ourselves.

Therefore, in this article, we’ll explore strategies for identifying bias regardless of the source. Once we know what to look for, we will be better able to identify bias when we see or hear it. Not only is it important that we master these skills ourselves, but it’s equally important to teach these to our students, so they can successfully navigate the bias that surrounds them.

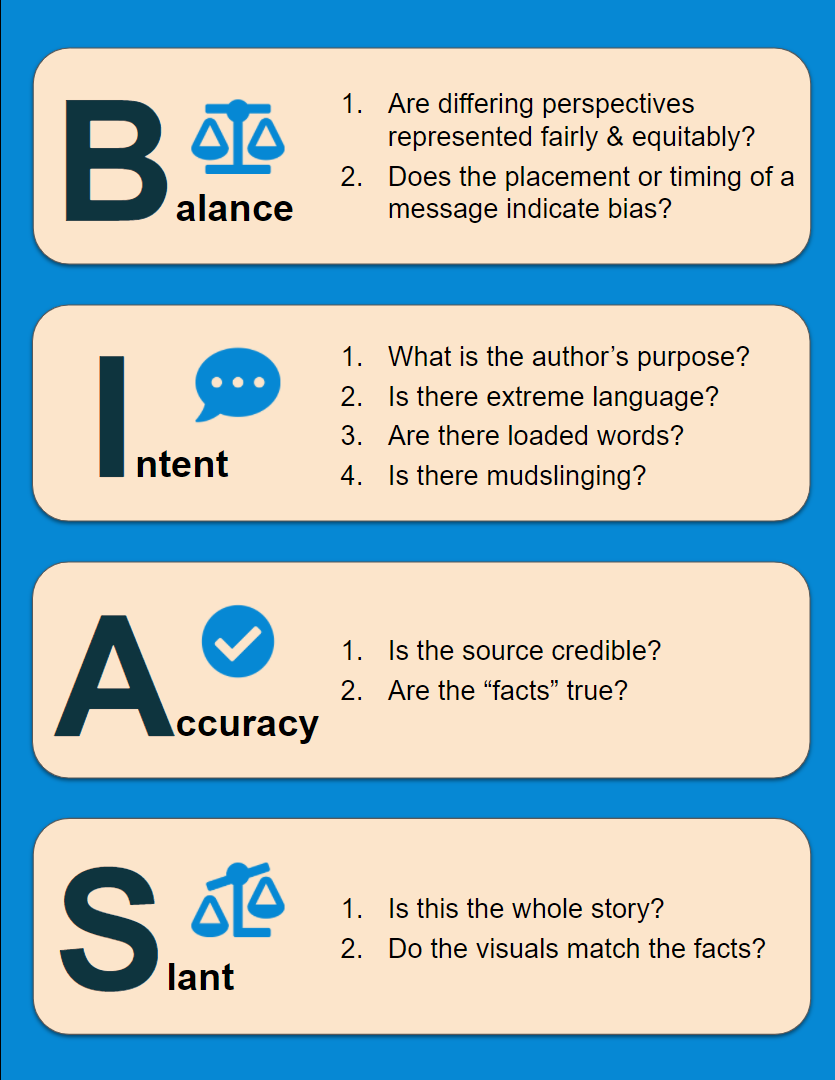

While there are many ways to explore the elements of bias, we’ll organize our ideas under the acronym of BIAS. This may help your students better remember the big ideas. Within each category, you will find more specific strategies and identifiers.

Use this poster with your students to remind them how to check for bias.

A significant contributing factor in biased messaging is that the communicator favors one side of an argument over another. Similarly, they value one set of evidence more than another. In many ways, balance is at the heart of bias. When we are biased about something, we are often not adequately seeking to discover all the information available about a topic or issue.

In our increasingly partisan world, this lack of balanced perspective has become a significant source of bias. People often choose to watch the same news station every day, thus getting only a limited perspective or set of facts. Similarly, people of like mindsets often associate with one another, having like conversations and sharing similar information. This closed circle of information perpetuates the biases held by the members of the group. When we only hear one side of the story, it’s nearly impossible to avoid bias.

The concept of balance is at the heart of quality journalism. We say news should be “fair and balanced,” and when we say this, we’re essentially saying that it should be unbiased. To make sure that the information we consume is genuinely fair and balanced, we can ask a few guiding questions.

Are differing perspectives represented fairly and equitably?

This question frames the essential concept of balance. If only one side is represented, it is clearly unbalanced. However, sometimes exploring two sides is not enough either. Many issues and topics are more complex than two evenly divided sides. In fact, seeing arguments as black and white (or simply this or that) oversimplifies most issues and can be part of the problem.

There are two parts to this question: fair and equitable. Fair would presume that the information is accurate and agreed upon by most with a similar perspective. Equitable would indicate that each voice and perspective is heard with equal emphasis.

In journalism, inequitable coverage is sometimes referred to as “overreporting” or “underreporting.” Focusing a large amount of time and content on a relatively small story would be an example of overreporting and makes the story seem more important than it really is. On the flipside, running only limited coverage about a topic that impacts many people could be considered underreporting and diminishes the importance of that story. While overreporting and underreporting may at times be unintentional, there are also times when they are done intentionally in an attempt to sway an audience on an issue.

Does the placement or timing of a message indicate bias?

Stories placed at the top of a newspaper, website, or news program are considered the most important stories of the day simply because of their placement, and because of this, they get the most attention. In the newspaper business, the most impactful stories are put “above the fold,” where readers see them first. On a website, we can think of this as “above the scroll.” In addition to their prominent placement, these stories typically have the largest headlines and most prominent pictures as well. In short, they demand the most attention and get noticed most often.

The choice of what goes first or is highlighted most prominently is a reflection of bias. Something must go first, so something will be highlighted. This is inevitable, but if a pattern emerges, it may indicate a significant bias by the network, company, or individual sharing the message.

One current trend in online publications is to feature analysis or commentary at the top of a news feed as featured articles. Traditionally, the headline stories have been fact-based, so a casual consumer of information may not notice that they are reading an opinion piece rather than hard news. In some cases, this might be used in a deliberate attempt to pass off opinion as fact.

Timing matters, as well. Sometimes, negative information is shared on a Friday or the day before a holiday because fewer people will be paying attention to the news. In politics, a candidate may sit on a story until it will do the most damage to an opponent, or conversely, lessen personal impact. In news rooms, stories that are run during the late evening news get more emphasis than those run around the 5:00 time frame because networks know that there are more viewers at 10:00.

Words have power. They can inform, persuade, and even entertain. Understanding the intent of the message is important because it can help us interpret the language being used. If the message is intended to inform, we expect that it will not contain overt bias. If the intent is to persuade, we expect a certain degree of bias because we know that the intent is to shape our opinion about something. When the purpose is to entertain, bias used for humor can become hurtful if the joke comes at another’s expense. Whenever possible, we need to identify the intent of the message. Ideally, the author will be up front and state that intent. If the intent is unclear, we should be especially watchful for bias and how it is being used.

In the worst cases, messages are intentionally meant to incite negative behavior, like hate, violence, and discrimination. Though it’s possible to unintentionally incite negative actions in others, language and messaging that is intentionally meant to cause harm or unrest is the most significant and dangerous. Using biased messaging with the intent to incite action is a practice often used by extremist groups and cult leaders. That being said, some degree of negative bias may also be heard from the mouths of politicians, reporters, and even ourselves when we engage in uninformed conversations. Therefore, for us to be responsible consumers of information, we need to be able to recognize biased messages for what they are and not blindly believe the messages that we hear.

A few key questions can inform our processing about the intent of a message and help us recognize bias.

What is the author’s purpose?

Ideally, the author will indicate a purpose. By being honest and up front about the intent, we can better anticipate the degree of bias that we will encounter. For example, there will likely be more bias in an editorial piece than a news story. To honor this transparency, newspapers have traditionally separated opinion pieces into a distinct section of a publication, thereby differentiating it from the daily news. In fact, publications often physically separate opinion writers from news reporters to preserve the integrity of the reporting. It’s a reminder that news and opinion should not mix. On the other hand, if we cannot determine the intent of a message, or worse yet, if it’s intentionally deceptive, we must be much more careful about identifying bias buried in the messaging.

Does the message contain extreme or inappropriate language?

Extreme or inappropriate language can incite disobedient behavior. In the worst cases, this is intentional. Vulgar words or phrases associated with extremist viewpoints are often used to appeal to emotions rather than reason. This use of language can lead a misinformed audience to harmful or violent action. While not always true, extremist language and vulgar word choice can also be a sign that the facts do not support the viewpoint. Speakers and writers may use this type of language to elicit an emotional response that redirects people away from the facts.

Does the message contain loaded words?

Loaded words are words that are used to elicit an emotional response because of the connotations connected to them. For instance, labeling a person or group of people as “radical” implies extremism, as this is a word loaded with many assumptions and connotations attached to it. Loaded words are often used by extremist groups, those who wish to redirect an audience from the facts, or those who seek an emotional response to their message.

Can the message be considered mudslinging?

Another negative intent is to use language to intentionally damage someone’s reputation. Mudslinging is a term used when someone “slings mud,” or makes derogatory statements about someone else. This may include sharing unsubstantiated claims, providing misleading facts, or under sharing certain perspectives. Those who engage in this behavior can ultimately be charged with libel or slander in court.

Our students are taught early on that there are differences between facts and opinions. However, these differences can often get blurred in biased messages. Because of this, we need to be intentional about checking the accuracy of the information we are consuming. In many ways, accuracy of information is the most foundational skill in beginning to recognize bias. If we don’t know that the information is false or misleading, it’s much more difficult to see it as bias. However, if we can identify information as being inaccurate or founded more on opinion than fact, we are more well equipped to identify biased messaging.

Is the source credible?

With this question, we are essentially asking where the information comes from and if we can trust it. This is a central question when trying to judge the accuracy of information. Who is the author? Can we trust the source of this information? What is the history of that source? Have they established a positive or negative reputation based on prior information they’ve shared? Where do they get their information, and do they support it with quality sources and practices? These questions and more can help us determine whether a source is credible.

One common persuasion tactic used to deflect an audience from a questionable source is the use of “general attributions,” rather than naming an actual person. For instance, “critics say” doesn’t give us any way to check on the credibility of the source. On the other hand, if a specific person or organization is named, we can do our own research and determine the accuracy of the claim.

Are the “facts” we are consuming true?

In addition to questioning the credibility of the source, we must also look at the information itself. First of all, is it actually a fact or simply an opinion shared as a fact? Many times, biased information tries to pass off opinion as fact. One persuasion strategy is called “mind reading.” When using this approach, the source will say things like, “Everybody agrees with me” or “I know you understand how important this is.” These statements assume that the speaker knows what others are thinking. By stating it as a fact, they hope that listeners accept it as truth.

Another common approach to biased messaging is to make a claim but fail to support that claim with any evidence at all. Other times, a limited amount of evidence is presented, but it is incomplete, insufficient, misleading, or inaccurate. In any case, we must assume the responsibility of determining if the evidence is accurate or not, especially when sources are not provided.

The tactic of providing only partial information can be a powerful way to bias a message. It’s easy to cherry-pick certain statistics, quotes, and facts to make our opinions sound convincing. The recent use of the term “alternate facts” is essentially an acknowledgment that facts can be used to shape and misrepresent an argument in different ways. As consumers of this information, we must determine two main things: Is the information presented true, and is it being used in a way that accurately conveys the original intent of that information? It’s easy to use something out of context to make it sound like something other than what it was intended. It is up to us to be critical consumers of these messages and determine what is simply misleading and what is actually true.

To help with this process, we can use fact-checking sites. These organizations investigate popular and controversial claims:

In some ways, slant is another word for intentional bias. When someone slants a message, they only tell part of the story—cherry-picking the information that helps sell their idea and ignoring anything that may contradict them. When someone is reacting to an event or responding to an accusation, this might be referred to as “spin.” How can I spin the facts to make them seem more favorable to my situation or point of view? When spinning or slanting the message, the communicator will often use many of the techniques mentioned in the first three parts of our BIAS formula. However, there are a few other key questions to consider, too.

Is this the whole story?

This is probably the most important question when identifying a slanted message. Are you getting the whole story, or are parts being either overemphasized or left out? In a slanted message, this inclusion and omission of information is intentional and meant to persuade. Handpicked facts are used to support a specific point of view.

Do the visuals match the facts?

One way to slant a message is to present misleading visuals. For instance, showing a new home being built might deflect a message that the housing market is suffering. What we “see” doesn’t match the message, and people often believe what they see more than what they hear. Similarly, the facial expression on the person captured in a picture can influence perception. Did the publisher choose a photo that is flattering or unflattering? This is often an intentional choice. If the person looks grumpy or angry, we get a very different feel than if they are shown smiling and happy.

Statistics can also be misrepresented in misleading charts and graphs. When comparing numbers, it’s important that the same scale is used for both. Using different scales for contrasting graphs can skew the interpretation of the numbers. For instance, if one shows increments of 1,000 and another shows increments of 10, the second will visually appear to be much more dramatic than the first.

Headlines and titles can be powerful, too. Do they include loaded words that color our feelings about the article, even before we read it? Do the headlines accurately match the message and the facts included in the article? Since many people only read the headlines, a misleading headline might be the only message communicated.

Extend Your Learning

- Challenging Confirmation Bias (Common Sense Education)

- Understanding Bias (Checkology)

- Recognizing Bias (NewseumED)

- Today’s Students Can’t Identify Fake News, Says Study (WeAreTeachers)

- News Literacy Resources for Classrooms (Common Sense Education)